The trial court decided an anti-SLAPP motion without a hearing, but the Court of Appeal concluded in *Chang v. Brooks* (2D3d, Mar. 14, 2025, No. B320278) (nonpub. opn.) that, while it is error not to give litigants the due process of a hearing, that error was not reversible without a showing of prejudice. In this restraining-order case, the defendant filed an anti-SLAPP motion. The trial court said there would be no oral argument unless requested, and ruled against the defendant. And it was unclear, the Court of Appeal noted, whether the defendant had a meaningful opportunity to object to the lack of a hearing.

But still no reversal. Even assuming it was error not to give the defendant a hearing on this substantive right, the defendant still has to show the error resulted in prejudice. That means he needed to explain what difference a hearing would have made. And he failed to do that on appeal.

The court cited two published cases for the proposition that being denied a hearing, by itself, is not reversible. (Bravo v. Ismaj (2002) 99 Cal.App.4th 211, 219, 225–227 [even where party was entitled to a hearing to declare him a vexatious litigant, there was no prejudice from the failure to hold one]; Mediterranean Construction Co. v. State Farm Fire & Casualty Co. (1998) 66 Cal.App.4th 257, 267 [even though there is a right to oral argument on a summary judgment motion, there is no per se rule requiring reversal, and prejudice is “an important element”].)

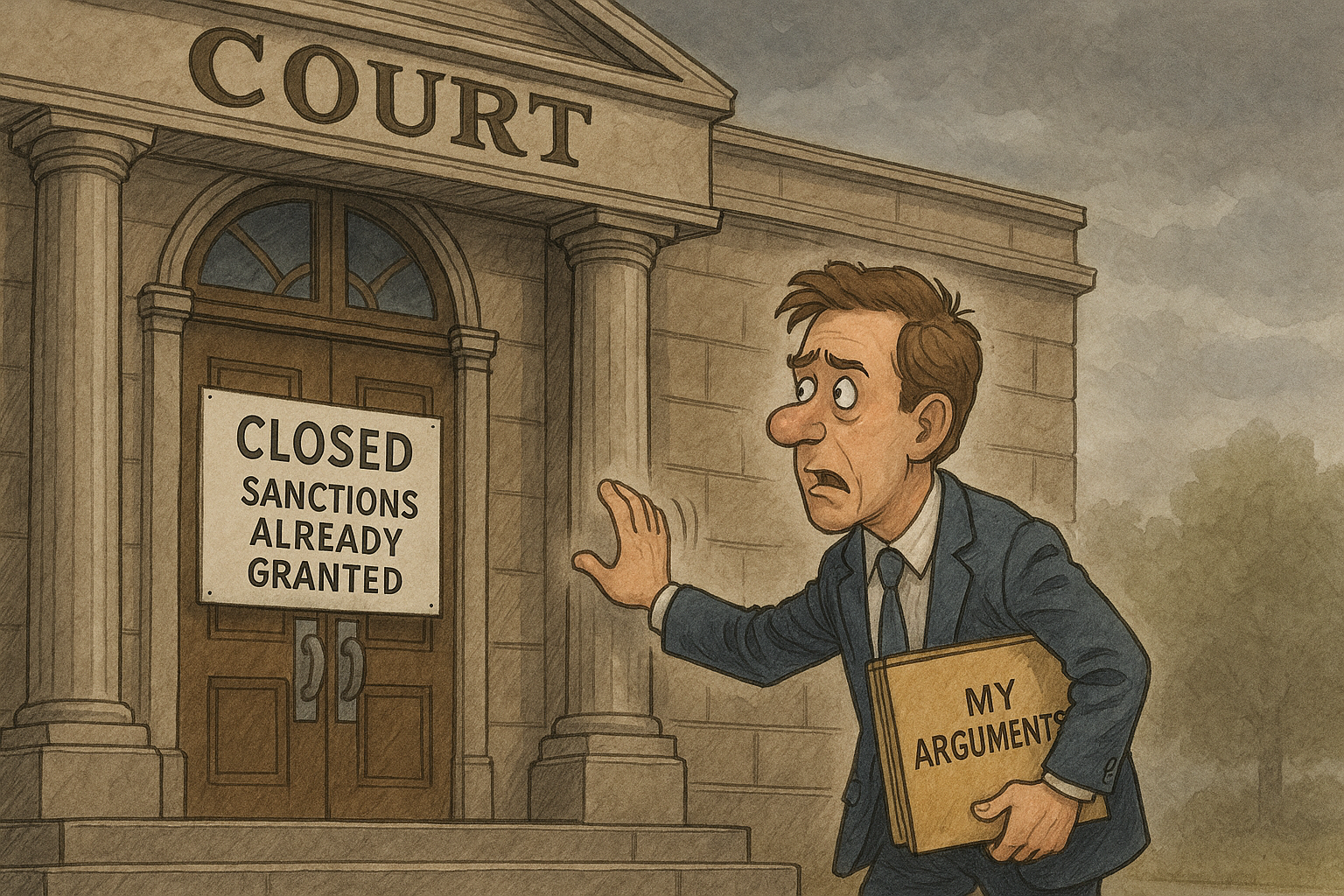

Whenever the court commits an error, ask this simple question: “So what?” Yes, the courts are supposed to follow the rules. But do you have any idea how many rules there are? Too many for anyone to understand or follow all the time. Even courts. Before a judge’s error can be reversed, the California Constitution requires a showing that it resulted in a “miscarriage of justice.” So if your judge made a mistake, figure out how to show that it made a difference. Otherwise, it will come to nothing.