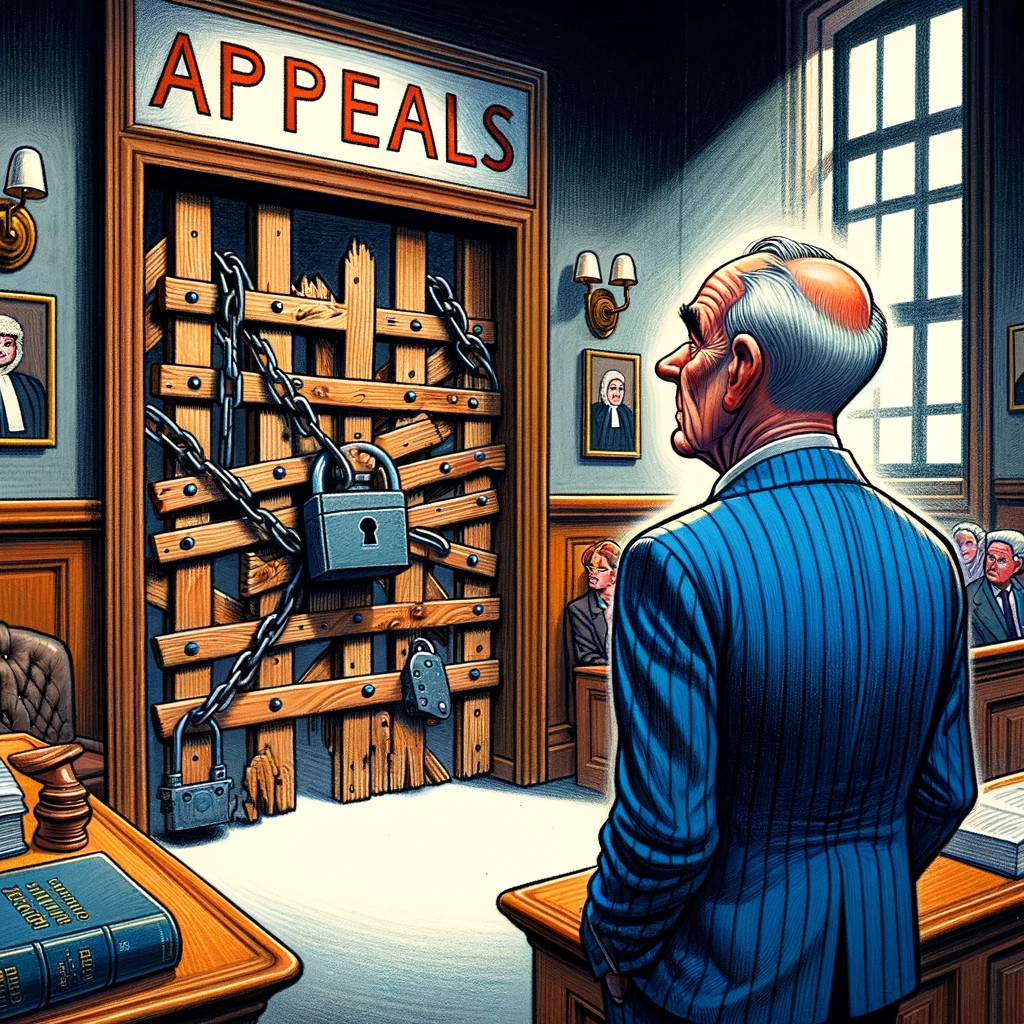

If you want to challenge a sanctions award over $5,000, you have to appeal now—if you wait, you lose. So when a discovery referee in Glickman v. Krolikowski (4D3d, Mar. 7, 2025, No. G064853) 2025 WL 732088 [pub. opn.] allocated most of the discovery costs to Krolikowski, he did the smart thing and appealed. After all, other than the sanctions statutes, there appears to be no other statute that authorizes the court to cost-shift discovery fees. So even though the referee didn’t mention the word “sanction,” what else could it be?

Dismissing, the Court of Appeal disagreed. “Courts may impose monetary sanctions only when authorized by statute or rule of court,” and “An order allocating discovery referee fees is not a sanctions order,” and the referee did not call it a sanction.

Instead, the order was one for “referee apportionment fees.” The rules governing apportionment of those fees—Code of Civil Procedure section 639 and California Rules of Court, Rule 3.922(c)—give the court discretion to allocate based on “the circumstances of the case” and “ability to pay.”

Can the court exercise that discretion to dole out would would be, in any other context, a sanction? The answer to that question will have to await the appeal following a judgment.

Whether a cost award might be deemed a “sanction” is an important and interesting one because it raises vexing procedural questions. For one thing, as in this case, it raises the question whether the order is appealable under section 904.1(a)(12). Or in the question of costs-of-proof for failing to admit a request for admission, the cost award is not a sanction. This means, as it did here, that the award is not independently appealable. It also probably means there is a lighter burden of proof—no showing of bad faith or misuse of discovery needed.

The upshot is that, while no one likes to get sanctioned, giving trial courts authority for cost-shifting that is non-reviewable until the end of the case presents a risk of abuse, as appears to happen sometimes in costs-of-proof cases. (See prior post here.)