Russell Lynwood Austin murdered his pregnant ex-girlfriend in her apartment with her two-year-old present. Austin slit her throat so violently that he nearly decapitated her. Austin then fled, leaving her bloody body, and her dying fetus, with the naked two-year-old child. The D.A. charged Austin with double-homicide and sought the death penalty.

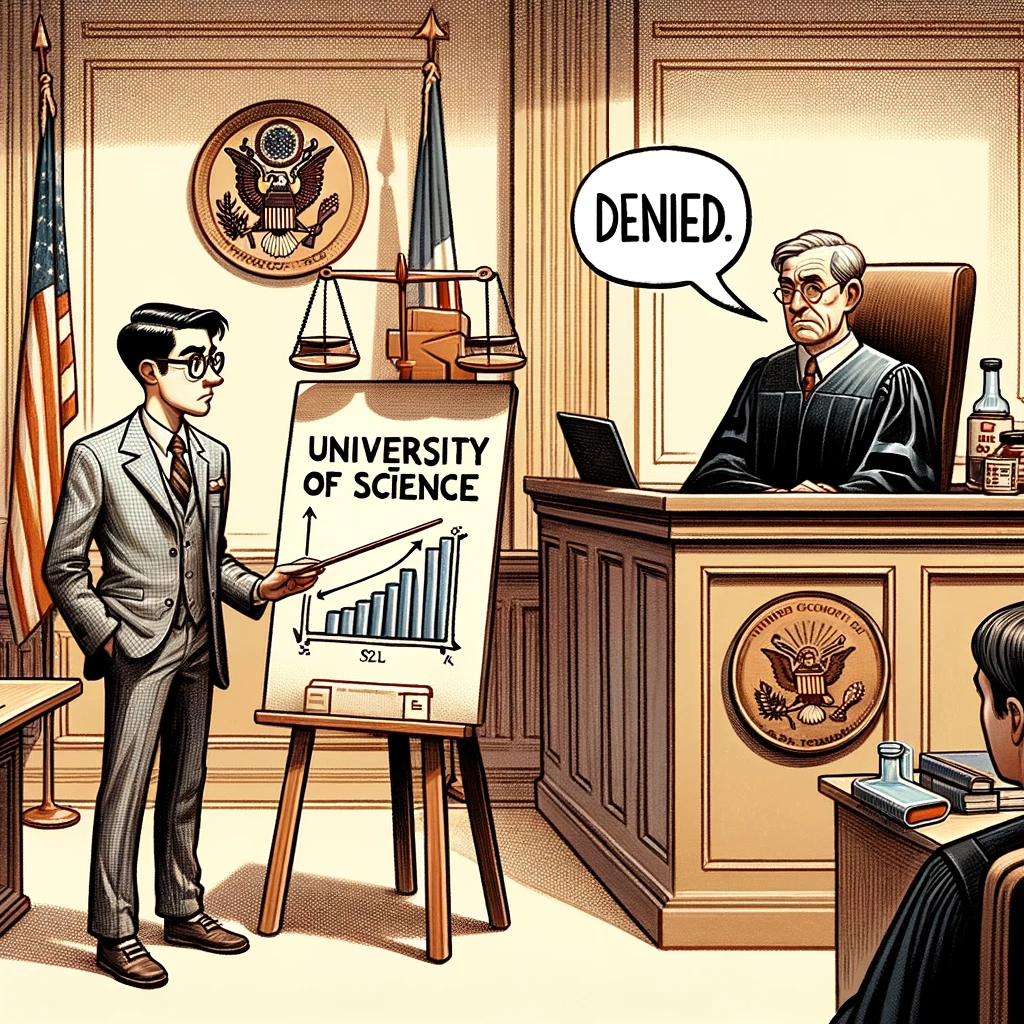

But Austin is a racial minority and thus entitled to the protections of the Racial Justice Act. He challenged the death sentence, citing crimonology statistics on race disparities in charging and sentencing. The trial court denied the motion, ruling that statistical analysis alone did not meet the threshold showing. The majority in Austin v. Superior Court (D2d2 Jan. 25, 2024 No. E080939) basically agreed, but remanded for an evidentiary hearing.

Under the Racial Justice Act, a defendant challenging the charges or sentencing against him must satisfy the following two-prong test: (1) that the defendant personally was being charged more harshly than similarly situated defendants of other races or ethnicities; and (2) statistical evidence shows a historic pattern of racial inequality in the jurisdiction’s capital charging practice.

The problem was that, on prong one, the Legislature had provided no guidance how to show the defendant “personally” was charged more harshly than “similarly situated” nonminorities.

The defendant, along with several law professors including Erwin Chemerinsky, argued that a defendant should be able to establish both prongs using merely statistical evidence. But the majority disagreed. After all, statistics merely show the charges, the sentence sought, and the race of the defendant—not the facts indicating the ruthlessness of the act in relation to other cases.

While declining to create a bright-line rule, the court concluded that showing similar conduct likely “requires some sort of review of the underlying facts of the other cases.” Mere statistical evidence was not enough here—but in another case, it might be.

The court issued a writ of mandate directing the trial court to hold an evidentiary hearing “to consider all of the relevant factors in charging and allow the District Attorney to present race-neutral reasons for the disparity in seeking the death penalty.”

Justice Menetrez concurred to say that he would hold that statistical evidence is enough to establish the ‘similar conduct’ threshold.

While the Austin majority puts more burden on the defendant than merely to recycle the same race-and-crime stats in every case, defendants still have enormous rights under the Racial Justice Act. To get the evidence to make his motion under the Act, the defendant can get the law-enforcement agency to cough up any information that is “relevant to a potential violation” of the Act. Young v. Superior Court of Solano County (2022) 79 Cal.App.5th 138. As Brenda Star Adams reported in the Daily Journal, “public defenders share anecdotally that raising violations of the Act is resulting in better plea offers from prosecutors.”

So if the Riverside County District Attorney has any information about times it did not seek the death penalty when a nonminority nearly decapitated his pregnant ex-girlfriend in front of her two-year-old, California affords Austin an absolute right to discover it.