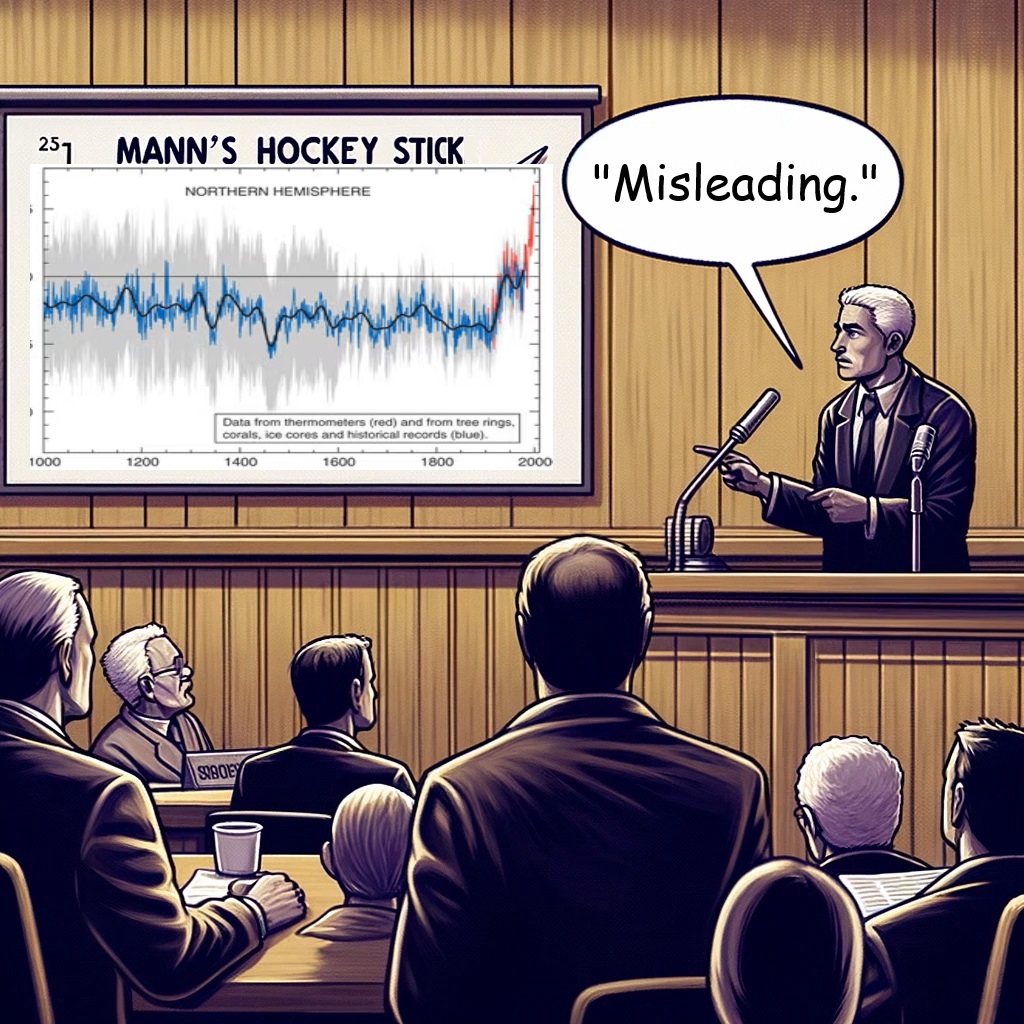

Wealth, class, and high office don’t buy a lot of respect these days, but people listen if you’ve got some extra letters hung on the end of your name as scientists do. So climate scientist Michael E. Mann, Ph.D, sued for defamation when Rand Simberg and Mark Steyn called his “hockey stick” graph the product of manipulated data. The hockey stick, published in the late ‘90s, showed global temperatures holding steady for hundreds of years and then dramatically spiking in the 19th century.

This is a D.C. Superior Court case, and the jury trial is not over yet. You can listen to actor reenactments of highlights of the trial using verbatim transcripts at the podcast Climate Change on Trial, hosted by Ann McElhinney and Phelim McAleer. After listening to the re-enactments, I have a few reactions.

The trial court denied the defendants’ anti-SLAPP motions. Although public comment on global warming (or climate change) is certainly protected, the court ruled that Mann deserved a trial. Specifically, Mann was entitled to try to prove that when Simberg and Steyn accused him of manipulating the data on global warming—such as by leaving out the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age—and that when they accused U. Penn’s academic-fraud investigation of him as whitewashed by linking it with that same university’s contemporaneous whitewashed investigation into (now-convicted) serial child-molester Jerry Sandusky—that they knew or recklessly disregarded the legitimacy of the Hockey Stick and thus acted with “malice.”

One lesson I draw after listening to the reenactments thus far is this: If you, as the plaintiff, are going to drag a public debate into a courtroom, the court will not be happy about it if you don’t focus the scope down good and narrow. Mann’s team does not appear to have done much to avoid turning this trial into a trial about climate change. After 12 years of waiting, a D.C. jury is now headed toward deciding Mann’s case by deciding whether one of the most famous symbols of climate change is open to legitimate debate. Turns out, there is, as the jury and observers have learned after two weeks of trial (though one need not have waited 12 years for that). And because the difference of opinion is and was legitimate, there is no legal “malice.” Mann is going to lose.

But ever since the “97% of scientists agree” moment, it has been déclassé to suggest there is a difference of opinion on climate science. And the trial court surely does not want to have to hand in a court-stamped piece of work product that will be waved around in political hearings and Twitter threads. In this case, Simberg is a rocket scientist, and Steyn an accomplished journalist as well as litigant. So the court probably would have preferred that, if Mann insisted on pursuing his suit, he find a way to let the court decide it on a legal issues and not scientific ones.

As an appeal is certain no matter who wins, here are two observations and a prediction:

Takeaway: If you are preparing for trial that involves a major public issue, avoid putting the judge in an untenable position. Most judges will want to compartmentalize the legal issues from the public issues, and try to decide the former and not the latter. If you’ve framed your case so that the only way you can win the legal issues is by winning the public issues, expect the judge to look for another way to decide your case—and it likely will not be in your favor.